History of Basque whaling

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Basques were among the first to catch whales commercially, as opposed to aboriginal whaling, and dominated the trade for five centuries, spreading to the far corners of the North Atlantic and even reaching the South Atlantic. The French explorer Samuel de Champlain, when writing about Basque whaling in Terranova (i.e. Newfoundland), described them as «the cleverest men at this fishing».[1] By the early 17th century, other nations entered the trade in earnest, seeking the Basques as tutors, «for [they] were then the only people who understand whaling», lamented the English explorer Jonas Poole.

Having learned the trade themselves, other nations adopted their techniques and soon dominated the burgeoning industry – often to the exclusion of their former instructors. Basque whaling peaked in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, but was in decline by the late 17th and early 18th centuries. By the 19th century, it was moribund as the right whale was nearly extinct and the bowhead whale was decimated.

Bay of Biscay

Beginnings

There is a document, a bill, which states in the year 670 a delivery of 40 «moyos» (casks of 250 liters) of «aceite de ballena» (whale oil) or «grasa de ballena» (whale blubber) was made from Bayonne to the abbey of Jumièges, between Le Havre and Rouen, for its use in illumination. The authors that assessed this document suggest for such a request to be made by such a distant monastery that Basque whalingmust have been well known – although the oil or blubber easily could have come from a stranded whale whose products were usurped by the church.[2]

Establishment and expansion

Another author contends that the first mention of the use of whales by the Basques came in 1059, in which year a measure was passed to concentrate whale meat in the market of Bayonne.[3] By the year 1150[Note 1] whaling had spread to the Basque provinces of Spain. In this year King Sancho the Wise of Navarre (r. 1150–94) granted San Sebastián certain privileges. The grant lists various goods that must be paid duties for warehousing, and among this list «boquinas-barbas de ballenas» or plates of whalebone (baleen) held a prominent place.[5] By 1190, whaling had spread to Santander.[3] In 1203, Alfonso VIII of Castile gave Hondarribia the same privileges that had been given to San Sebastian. In 1204, these privileges were extended to Mutriku and Getaria. Similar privileges were given to Zarautz by Ferdinand III of Castile in a royal order dated at Burgos 28 September 1237. This document also states that «in accordance with custom, the King should have a slice of each whale, along the backbone, from the head to the tail».[5]Whaling also spread to Asturias (1232) and finally to Galicia(1371).[3]

Up to 49 ports[Note 2] had whaling establishments along the coast from the French Basque country to Cape Finisterre. The principal target of the trade was what the French Basques called «sarde». It was later called the Biscayan right whale (Balaena biscayensis), and is now known as the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). It was caught during its migration from the months of October–November to February–March, with peak catching probably occurring in January.[3] They may have also hunted the gray whale(Eschrichtius robustus), which existed in the North Atlantic until at least the early 18th century.[6][7]Bryant suggests that if gray whales inhabited coastal waters like they do today in the North Pacificthey would have been likely targets for Basque whalers, perhaps even more so then the North Atlantic right whale – although most contemporary illustrations and skeletal remains from catches were of the latter species.[3] They may have also caught the occasional sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), as remains of this species were found in the old buildings used to try out the blubber into oil.[8]

Hunting methods

The whales were spotted by full-time look-outs from stone watchtowers (known as vigías) situated on headlands or high up on mountains overlooking the harbor, which limited the hunting area to several miles around the port. The remains of these vigías reportedly exist on Talaya mendi («Look-out mountain») above Zarautz and on Whale Hill in Ulia, San Sebastian, while the point on which the vigía in Biarritz was once situated is now the site of a lighthouse, the Pointe Saint-Martin Light (est. 1834).[9][10]

When the spout of a whale was sighted, the watchman alerted the men by burning some straw, beating a drum, ringing a bell or waving a flag. Once alerted, men launched small rowing boats from the beach, or, if the shoreline was steep, the boats were held by a capstan and launched by releasing the rope attached to the boats. The whale was struck with a two-flued harpoon (as shown in the seal of Hondarribia, dated 1297), lanced, and killed. A larger boat manned by ten men towed the carcassashore, waiting for high tide to beach the whale, where it was flensed. The blubber was then brought to a boiling house where it was rendered into oil.[11]

Tithes and taxes

According to the Laws of Oléron the whalemen of Biarritz, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, and the rest of the French Basque country were exempt from taxation, although they voluntarily gave the whales’ tongues to the church as a gift. It wasn’t until the kings of England, acting as the Dukes of Guyenne, that charges began to be enacted against them. In 1197, the future King John of England (r. 1199–1216)[12] gave Vital de Biole and his heirs and successors the right to levy a tax of 50 angevin livres on the first two whales taken annually at Biarritz, in exchange for the rent of the fishery at Guernsey. In 1257, William Lavielle gave the bishop and chapter of Bayonne a tithe of the whales caught by the men of the same port. This was paid until 1498. In 1261, an act of the Abbey of Honce announced, as a continuation of the tradition of giving the tongue as a gift to the church, a tithe was to be paid on the whales landed at Bayonne.[9] Under a 1324 edict known as De Praerogativa Regis (The Royal Prerogative), Edward II (r. 1307–27)[12] collected a duty on the whales caught in British waters, which included the French Basque coast.[13] His successor, Edward III (r. 1327–77),[12] continued this tradition by collecting a £6 tax for each whale taken and landed at Biarritz. In 1338, this was relinquished to Peter de Puyanne, admiral of the English fleet stationed at Bayonne.[14]

In Lekeitio, the first document to mention the use of whales in its archives, dated 11 September 1381, states that the whalebone procured in that port would be divided into three parts, with «two for repairing the boat-harbour, and the third for the fabric of the church.» A document of 1608 repeats this order. A similar order, dated 20 November 1474, said that half the value of each whale caught from Getaria should be given towards the repair of the church and boat-harbor. It was also custom in Getaria to give the first whale of the season to the King, half of which he returned. San Sebastián, in continuing an ancient custom, gave the whalebone to the Cofradia (brotherhood) of San Pedro.[5]

Cultural significance

The trade had reached such importance in the Basque provinces during this time that several towns and villages depicted whales or whaling scenes on their seals and coat-of-arms. This practice included Bermeo (dated 1351), Castro Urdiales (currently outside the Basque region), Hondarribia(1297), Getaria, Lekeitio, Mutriku (1507, 1562), and Ondarroa in Spain; and Biarritz, Guéthary, and Hendaye in France. Whaling was important enough that laws were passed in 1521 and 1530, barring foreign (re. French) whalers from operating off the Spanish coast, while in 1619 and 1649, foreign whale products could not be sold in Spanish markets.[3][8]

Peak and decline

The industry in the French Basque region never reached the importance it did in the Spanish provinces. Few towns participated and only a small number of whales were probably taken. From the number of extant documents and written references Aguilar (1986) surmised that French Basque whaling peaked in the second half of the 13th century, and subsequently declined.[3] Although whaling as a commercial activity had ended by 1567, some right whales were taken as late as 1688.[15] For the Spanish Basque region (Biscay and Gipuzkoa) the peak was reached in the second half of the 16th century, but as early as the end of the same century it was in decline. Subsequently, an increase in whaling activity appears to have occurred in Cantabria, Asturias, and Galicia in the first half of the 17th century. Here the Basques hired seasonal «land factories» (whaling stations), particularly in Galicia – the Galicians themselves were never whalers, they only built these installations so they could rent them out on an annual basis to the Basques.[8] The peak was short-lived. By the second half of the 17th century whaling in these areas was in general decline. The War of the Spanish Succession(1701–14) sounded the death knell for whaling in the Bay of Biscay, with the trade ceasing altogether in Cantabria (1720), Asturias (1722), and Galicia (1720). It only continued in the Spanish Basque region, where it barely survived.[3]

Catch

The total number of right whales taken by the Basques in the Bay of Biscay is unknown, as serial catch statistics weren’t compiled until the 16th century. Incomplete catch statistics for Lekeitio from 1517 to 1662 show a total catch of 68 whales, an average of two-and-a-half a year.[8] The most were caught in 1536 and 1538, when six were taken in each year. In 1543, whalemen from Lekeitio injured a whale, but it was captured by the men of Mutriku, resulting in the whale being divided between the two towns. The same year a mother-calf pair were caught. On 24 February 1546, a whale was reportedly killed in front of St. Nicholas Island. In 1611, two small whales were killed by the men of Lekeitio and Ondarroa, which resulted in a lawsuit.[5] Similar records exist for Zarautz and Getaria. Fifty-five whales were caught from Zarautz between 1637 and 1801,[5] and eighteen from Getaria between 1699 and 1789.[8]

Although whaling in the Basque regions was carried out as a cooperative enterprise among all the fishermen of a town, only the watchmen received a salary while there was no whaling. With such a low economic investment, «profits from a single whale would have been enormous, since their value was very high in those days.»[3] In such circumstances a catch of one whale every two or three years for each port may have kept the trade alive. Coming to a conclusion on the number of whales caught along the entire coast in a single year, as Aguilar has noted, is a more difficult matter. Even though 49 ports have been identified as whaling settlements, they didn’t all participate in the trade at the same time, as it is known that some ports only hunted whales for a short period of time. Also, no details exist of the operations of small galleons that caught whales in the Bay of Biscay – especially off Galicia – without a station ashore. Aguilar suggests the total yearly catch may not have exceeded «some dozens, possibly reaching one hundred or thereabouts.»[3]

Composition of catch and possible reasons for decline

Despite the seemingly low annual harvest, two factors must be taken into consideration when discussing the decline and later (nearly) complete disappearance of right whales in the region: one, the preference of Basque whalers to target mother-calf pairs; and two, exploitation of the species outside the Bay of Biscay.

The Basque whalemen directed most of their attention to attacking calves, given they were easily captured and, when struck, allowed them to approach the mother, who came to its aid, only to be killed herself. To encourage such methods, the harpooner and crew that wounded the calf first was rewarded a greater share of the profits.[3][8] Of the 86 whales caught from Getaria and Lekeitio, up to 22% were calves. Such hunting methods would have had «detrimental consequences» for the species. The second factor may have been even more devastating to right whales, given the stock identify of this species is unknown.[3] There may have been a large population extending throughout the North Atlantic, meaning a single population would have been taken in several areas at the same time, as this species was the main target of operations in New England,[16] New York,[17] Iceland, Northern Norway,[18] and elsewhere from the early 17th century onwards. It was once thought that this species was also the main target (or at least represented half the catch) in southern Labrador, but it now appears as though bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) were the primary targets.[19]

If a small, discrete stock had existed in the Bay of Biscay, then localized hunting by the Basques may have led to its over-exploitation and subsequent (near) disappearance there. A third possibility, perhaps the most plausible, would be that there are (or were) two populations, one in the western North Atlantic and the other in the eastern North Atlantic. Such a view would conform well with the mainly coastal distribution of right whales in the western North Atlantic today. Still, this possibility would result in the harvest of right whales not only in the Bay of Biscay, but in Iceland, Northern Norway, and the rest of Europe, which may have been enough to severely deplete this supposed stock.

Decay

Only four whales were reportedly caught in the Bay of Biscay in the 19th century, and at least one more was struck but lost and another chased unsuccessfully. The first was caught off Hondarribia in 1805, the second off San Sebastian in 1854, the third off Getaria-Zarautz in 1878, and the last off San Sebastian in 1893.[8] In January 1854, three whales (said to be a mother and her two calves) entered the bay of San Sebastian. Only one of the calves was caught. The whale caught off Getaria-Zarautz was taken on 11 February. Several boats were sent out of both ports, along with one from Orio. The whale was struck with a harpoon from Getaria, but the line belonged to Zarautz. This resulted in a lawsuit, which led to the whale being left to rot ashore. The unpleasant smell of the decomposing carcass led to it being blown up. In 1844, a whale was struck off Zarautz, but, after being towed for six hours, the line was broken, and the whale was lost with two harpoons and three lances in its body. Another whale was seen off Getaria early in the morning on 25 July 1850, but the harpooner missed his mark, and the whale swam away to the northwest.[5] On 14 May 1901, a 12 m (39 ft) right whale was killed by fishermen using dynamite off the town of Orio,[20] an event reflected in a folk poempopularized by singer-songwriter Benito Lertxundi.[21] A local festival representing this catch have been held on 5 year intervals.[22] Only a few more sightings of right whales were made in the area, the last in 1977, when the crew of a Spanish whale catcher sighted one at about 43° N and 10° 30′ W.[3][8][20]

Newfoundland and Labrador

Early claims

In his History of Brittany (1582), the French jurist and historian Bertrand d’Argentré (1519–1590) was the first (as far as we currently know) to make the claim that the Basques, Bretons, and Normanswere the first to reach the New World «before any other people».[2][23] The Bordeaux jurist Etienne de Cleirac (1647) made a similar claim, stating that the French Basques, in pursuing whales across the North Atlantic, discovered North America a century before Columbus.[24] The Belgian cetologistPierre-Joseph van Beneden (1878, 1892) repeated such assertions by saying that the Basques, in the year 1372,[Note 3] found the number of whales to increase on approach of the Newfoundland Banks.[2][3]

Beginnings and expansion

The first undisputed presence of Basque whaling expeditions in the New World was in the second quarter of the 16th century. It appears to have been the French Basques, following the lead of Breton cod-fishermen that reported finding rich whaling grounds in «Terranova» (Newfoundland and Labrador). The Basques called the area they frequented «Grandbaya» (Grand Bay), today known as the Strait of Belle Isle, which separates Newfoundland from southern Labrador. Their initial voyages to this area were mixed cod and whaling ventures. Instead of returning home with whale oil, they brought back whale meat in brine. The French Basque ship La Catherine d’Urtubie made the first known voyage involving whale products in 1530, when she supposedly returned with 4,500 dried and cured cod, as well as twelve barrels of whale meat «without flippers or tail» (a phrase for whale meat in brine). After a period of development, expeditions were sent purely aimed at obtaining whale oil. The first establishments for processing whale oil in southern Labrador may have been built in the late 1530s, although it wasn’t until 1548 that notarial documents confirm this.[24]

By the 1540s, when the Spanish Basques began sending whaling expeditions to Terranova, the ventures were no longer experimental, but a «resounding financial success from their inception.» By the end of the decade they were delivering large cargoes of whale oil to Bristol, London, and Flanders. A large market existed for «lumera», as whale oil used for lighting was called. «Sain» or «grasa de ballena» was also used (by mixing it with tar and oakum) for caulking ships, as well as in the textile industry.[25] Ambroise Paré (1510–90), who visited Bayonne when King Charles IX (r. 1560–74) was there in 1564, said they used the baleen to «make farthingales, stays for women, knife-handles, and many other things».[26]

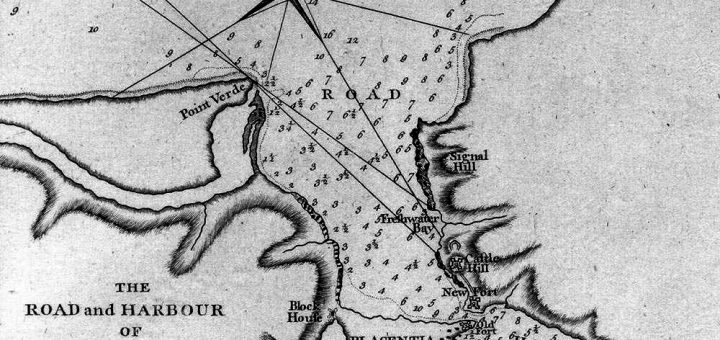

Most documents dealing with whaling in Terranova concern the years 1548 to 1588, with the largest quantity dealing with the harbor of Red Bay or «Less Buttes» – both names in reference to the red granite cliffs of the region. The references include acts of piracy in the 1550s, the loss of a ship in 1565, a disastrous wintering in 1576–77, and, on Christmas Eve 1584, a will written for a dying Basque, Joanes de Echaniz; the first known Canadian will. The last overwintering in Red Bay was made in 1603.[25] During their onshore stays, the whalers developed relations with American natives that led to the establishment of a purpose-specific language with both American native and Basque elements.

Wrecks

In 1978, the wreck of a ship was found in Red Bay. She is believed to be the Spanish Basque galleonSan Juan, a three-masted, 27.1 m (90 ft) long, 250–300-ton vessel that was lost in 1565. San Juan, carrying a cargo of nearly 1,000 barrels of whale oil, was wrecked by an autumn storm. She grounded stern first on the northern side of Saddle Island, struck the bottom several times and split her keel open before sinking 30 yards from shore.[27] Her captain, Joanes de Portu, and crew were able to save the sails, rigging, some provisions, and about half the whale oil. The crew took to the boats and hailed another ship for a ride back to Spain. The following year de Portu salvaged more of the wreck before she finally sank out of sight.[11] Three more wrecks have been found in Red Bay, the last in 2004.[28] The charred hull fragments of the second ship, found in 1983, strongly suggest the ship sank because of a fire.[27]

Hunting methods, culture, and archaeology

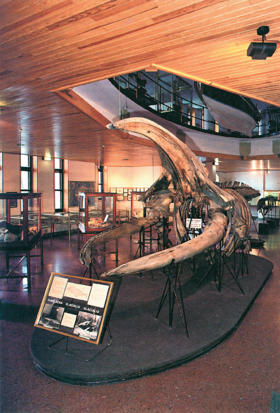

Two species of whale were hunted in southern Labrador, the North Atlantic right whale and the bowhead whale. The former were taken during the «early» season in the summer, while the latter was caught from the fall to early winter (October–January). DNA analysis of the old bones after a comprehensive search of Basque whaling ports from the 16th to the 17th century, in the Strait of Belle Isle and Gulf of St. Lawrence found that the right whale was by then less than 1% of the whales taken.[29] During the peak of Terranova whaling (1560s–1580s) the Spanish Basques used well-armed galleons of up to 600–700 tons, while the French Basques usually fitted out smaller vessels. A 450-ton Basque ship carrying 100 or more men required about 300 hogsheads of cider and wine and 300–400 quintals of ship’s biscuit, as well as other dry provisions. In Labrador the men subsisted mainly on locally caught cod and salmon, as well as the occasional caribou or wild duck. This diet was supplemented with dried peas, beans, chickpeas, olive oil, mustard seed, and bacon.[25] Before leaving for Terranova sometime in the months of May or June, a priest went aboard the ships to bless them and say a special mass for the success of the expeditions. Sailing across the stormy North Atlantic must have been a very unpleasant experience for the crew of up to 130 men and boys, as they slept on the hard decks or filthy, vermin-invested straw palliasses. Halfway there the smell of refuse in the bilge would have been unbearable.[11] After a voyage of two months the ships would anchor in one of the twelve harbors on the southern shore of Labrador and eastern Quebec. Archaeological evidence has been found for ten of these harbors – Middle Bay and Blanc-Sablon in Quebec, and Schooner Cove, West St. Modeste, East St. Modeste, Carrol Cove, Red Bay, Chateau Bay, Pleasure Harbour, and Cape Charles in southern Labrador.[30] Once the ice had disappeared the ships entered the harbors where the coopers went ashore and erected their dwellings and workshops, while most of the crew lived aboard ship.[11] The boys were also sent ashore to chop wood and prepare meals.[31]

In these bays the men constructed temporary whaling stations to process the whale blubber into oil. The tryworks were built close to the shore facing the harbor. They consisted of up to seven or eight fireboxes usually made of local granite – but on occasion containing imported sandstone or limestone ballast rock – backed by a heavy stone wall and common side walls. More fireboxes were built than were used at once, as the local granite quickly deteriorated after exposure to a wood fire. It appears that once a firebox had lost its usefulness, the men merely shifted the trypot to a «spare» firebox to continue processing the oil. Behind the main wall were wooden platforms where men would ladle the oil from the trypots into vessels filled with cold water used to cool and purify the oil. The foundations of the tryworks were mortared with local or imported fine clay and sheltered by a roof of red ceramic tiles supported by heavily framed wooden posts dug into the ground.[32]

On a small terrace overlooking the tryworks was a substantial tile-roofed building, the cooperage. While the cooper lived comfortably in this structure other crew members used smaller structures framed with wood and covered with cloth and baleen as sleeping quarters. Dozens of these dwellings have been found among the bedrock outcrops on Saddle Island. Here hearths were built in small niches in the rock that sheltered the men from the wind.[32]

In 1982, archaeologists found a whaler’s cemetery on the extreme eastern side of Saddle Island. Four subsequent summers of excavations revealed that it contained the remains of more than 60 graves, consisting of more than 140 individuals, all adult males in their early 20s to early 40s, with the exception of two twelve-year-olds. One burial contained the remains of a wool shirt and a pair of breeches – the former of which having been dyed with madder and the latter with indigo. The breeches were of thick, heavily teaseled wool, gathered at the waist and cut full at the hips, tapered to a tight fit at the knees, certainly making their owners warm and comfortable in the coastal tundra environment they had to live and work in, where the highest temperature (reached in August) was only 50 °F (10 °C). Another costume, recovered outside the cemetery, consisted of «a white knitted wool cap, an inner shirt and outer shirt or jacket made from white wool with a light brown plaid pattern, dark brown breeches, tailored stockings, and vegetable-tanned leather shoes.» Unlike the other pair of breeches, these were pleated at the waist and left open and baggy at the knees.[32]

At least sixteen stations have been found in Red Bay, eight on the northern side of the 3,000 m (3/5 mile) long Saddle Island at the entrance of the bay; seven on the mainland; and one on tiny Penney Island within the bay.[32] During the peak of the trade nearly 1,000 men could be found working in and around Red Bay, while as many as eleven ships resorted to this harbor in 1575, alone.[24] Three vigías were built on Saddle Island, one on the western side of the island near or on the present site of a lighthouse, the second on the eastern side at the top of a hill over 30 m (100 ft) in elevation, and the third on its eastern shore. There was also one placed on a 10 m (33 ft) high hill on the smaller Twin Island to the east.[30][32]

When a 8 m (26 ft) long whale was sighted, chalupas (chaloupes in French, and later shallops in English) were sent out, each manned by a steersman, five oarsmen, and a harpooner. The whale was harpooned and forced to tow a wooden drogue or drag, which was used to tire the whale. Once exhausted, the whale was lanced and killed. If darkness fell upon the crews before they returned, those ashore would light signal fires at the vigías to guild them back to the station. The whales were brought alongside a wharf or cutting stage, where they were flensed. The blubber was tried out, cooled, and poured into barricas – casks of oak that held 55 gallons of oil. These casks were towed out to the ship by a boat, where they were stored in the hold.[11] When a full cargo had been obtained, either during the right whale season, or, more often during the later bowhead season, many of the larger ships sailed to Pasaia to discharge their cargoes; they also fitted out of the same port. Pasaia was preferred by both French and Spanish Basques because of its deep-water entrance and the excellent shelter it provided from Biscay storms.[25][32]

Peak and decline

An intensive era of whaling began when peace was established after the Valois marriage (1572). An average of fifteen ships was sent to Terranova each year, with twenty being sent during the peak years.[25] Aguilar (1986), referring to the number of both Spanish and French Basque ships, said twenty-thirty galleons would seem fairly accurate.[3] Thomas Cano (1611) said more than 200 ships were sent to Terranova, although this is an obvious exaggeration.[3]

Ships from Red Bay alone sent 6,000–9,000 barrels of oil to Europe every year during the peak of exploitation, while a further 8,000 or 9,000 barrels was produced in St. Modeste, Chateau Bay, and other harbors. Each ship averaged 1,000 barrels a season, a cargo that rivaled the Spanish galleons bringing back treasure from the Caribbean for sheer monetary value.[30] So, on average, a minimum of 15,000 barrels of oil would have been produced each year, which would have involved a catch of at least 300 whales, or twenty per ship.[25]

By the 1580s, whaling was in decline, as ships returned to port half empty. This decade also coincided with the period when the king needed Spanish Basque ships for his armadas.[25] The trade was particularly affected in 1586, 1587, and 1588, when Spanish Basque ships and sailors were detained in preparation for the 1588 armada against England. The threat of such detentions continued to undermine Spanish Basque whaling into the 1590s and early 1600s.[24] Although whale stocks may have had a chance to increase in the 1590s and early 1600s with the diminution of the Spanish Basque fleet, it appears the French Basques may have taken up the slack of their counterparts of northeastern Spain. In April 1602, Saint-Jean-de-Luz alone sent seven ships to carry out whaling in Terranova.[9] Other factors, such as attacks by hostile Inuit(which, according to parish records, resulted in at least three instances of fatalities between 1575 and 1618), piratical attacks by the English and Dutch, and the opening of the Spitsbergen fishery (see below) may have also played a part in the decline.[25]

By 1632, they were finding it safer to hunt for whales out of the establishments at «Côte-Nord», such as Mingan and Escoumins and even as far south as Tadoussac at the mouth of the Saguenay River.[25]Despite this, Spanish Basque expeditions continued to be sent to Labrador, with voyages documented in 1622, 1624–27, 1629–30, 1632, and later.[24] As late as 1681 the port of Pasaia alone sent twelve whaling galleons to Terranova. The end came in 1697, when the Basques (apparently only the Spanish Basques) were prevented from sending out whaling expeditions to Terranova, while the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) finally expelled them from the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[3] Later the French Basques still sent whaling expeditions to Terranova, often basing them at Louisbourg.[25]