by Ander Izagirre

A 1615 decree enabled the killing of Basques in the Icelandic West Fjords district and no one remembered to repeal it till last April 22. The decree was enacted by Danish king Christian IV and enforced by Ari Magnússon, district commissioner, allowing the locals to hunt down the Basque whale hunters whose ships had just wrecked: they killed 32, the bloodiest massacre in the history of Iceland.

A reconciliation ceremony was held on April 22 in the village of Hólmavik, on the shore of the fjord in which the three Basque galleons sank. A memorial was placed on a volcanic rock, the Icelandic and Basque authorities delivered their speeches, a descendant of one of the murderers and a descendant of the murdered hugged, then they read poems, listened to music, visited an archaeological site. It turned out being nicer than the 1615 orgy of hackings, stonings, beheadings and dismemberments. Encouraged by such a good atmosphere, Mr. Jónas Gudmundsson, current West Fjord district commissioner, proclaimed the good news: the decree that allowed to kill Basques is repealed.

Then he explained he was joking. That is: it wasn’t allowed before either, they have laws in Iceland that forbid the killing of people in general, Basques in particular. But the 1615 order was still there, it was nice to repeal it, and now the Basque tourist will feel more comfortable visiting.

Things Went Well at First: ther Basque-Icelandic Pidgin Language

Not trying to make the Icelanders angry, now that we’re friends, but this is how it was: they couldn’t hunt whales. They just seized the ones that beached themselves on the shore. They finished them, ate their meat and used their bones to build their houses. The Icelandic term for wishing good luck to someone is hvelreki, a word that includes both the noun whale and the verb to beach. Good luck: may a whale get stranded on your beach.

18th century Basque whaler. Photo: Wikimedia

They didn’t use the whales on an industrial scale either, like the Basques did, who spread their fat melting oil factories along the North Atlantic, from the Svalbard islands to Newfoundland. Now, that was business: every barrel of whale oil was sold for the equivalent amount today to five thousand euros in Europe, and there were galleons that carried up to one or two thousand barrels to market each season.

When the Basques arrived in Iceland, they maintained good relations with the locals: they paid taxes for the right to hunt whales in their waters, for the right to disembark in dry land to quarter them and melt their fat, and for the right to collect wood. They were paid directly to the Icelandic leaders, which broke the monopoly of the king of Denmark, who ruled over Iceland. Moreover, the Basques and Icelanders bought and sold goods to each other. The Danish King started to become very annoyed.

The relationship between whalers and locals was a good and lasting one. The occurrence of a basic Basque-Icelandic language, what the experts call apidgin, proves it: a makeshift language, a casual attempt that in this case included Basque, Icelandic, English and French terms. Two 17th century lexicons gathering 745 words are kept in an Institute in Reykjavik: it’s the first dictionary of a different language, after Latin, in the history of Iceland. Many of the Basque terms come from the Lapurdian dialect (from the French-Basque province of Lapurdi), which implies that most of the whalers arrived from the Saint-Jean-de-Luz port.

Hundreds of individual words like schulaura (from the Basque eskularru: glove), eskora (aizkora: axe) o unat (hunat!: come here!) are gathered in the glossaries. And a good number of sentences: “Christ Maria presenta for mi balia, for mi presenta for ju bustana”. That is: “If Christ and Mary get me a whale, I keep the body and you keep the tail end.” Or something like that.

You could sort of put together a kind of dialogue with other phrases:

- Fenicha for ju (Fuck with you).

- Sumbat galsardia for? (In exchange for how many socks?)

- For ju mala gisonna (You’re a bad man)

- Gianzu caca (Go eat shit)

They were friends, but they sure talked like whalers.

How the Masscre Happened

Things took a bad turn in 1615. Iceland, probably the poorest European country, had endured several terrible winters and it was close to starvation. It had suffered pirate attacks as well. In fact, the first times the Basque whaling galleons showed up, they took them for attackers. That same spring, Danish King Christian IV issued the decree that ruled that Icelanders could attack the Basques, take their ships, pillage their goods and, if needed, kill them.

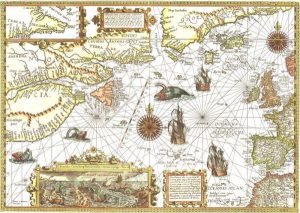

1592, Whale fishing areas of the North Atlantic. Photo: Wikimedia

That year three Gipuzkoan galleons arrived and settled in a west Icelandic fjord. There were some scuffles: a party of Icelandic fishermen attacked two whaling longboats stuck in the ice on a bay, “in order to acquire a certain fame by killing Basques”, according to Jón Gudmunsson, 17th century chronicler and author of the most detailed account of the massacre: “A True Account of Spanish Men’s Shipwrecks and Fighting”. An Icelandic farmer stole some whale oil, some Basques stole some sheep, and both sides became embroiled in small quarrels. Still, the campaign went well. The Basques hunted eleven whales, melted their fat and sold their meat, pretty cheap, to the Icelanders. Gudmunsson recounts that they even harpooned some small whales and gave them to the shore’s townsfolk.

On September 19, the three Basque captains did their math, closed the campaign, prepared their ships to return to San Sebastián and celebrated with red wine over dinner. That night disaster came: the storm, waves as high as walls, blocks of ice smashing the hulls, burst wood, the flooding, the galleons going down with their oil filled cargo holds. And ultimately, when the screams quietened, 83 men in dry land.

83 soaking wet, freezing men in dry land, under a storm, on a subarctic moor, with no food, no ships, and a six month winter ahead of them. There were some starving farmer and shepherd towns nearby, worn out by a relentless four-year-long winter, with the couple of skeletal sheep they had managed to keep alive.

Photo: Wikimedia

The sheep: Basque captain Martín de Villafranca intended to buy some. The Icelanders refused: they didn’t want to starve. Villafranca visited Pastor Jón Grímsson, reclaimed some Icelandic debts over a volume of whale oil he didn’t care for weeks ago and now was matter of life and death. Villafranca wanted the debt to be paid with sheep. The pastor replied he owed him nothing. Villafranca’s men took him, roughed with him, and put a rope around his neck, pretended to hang him, left him and went away.

This one would be the most serious accusation against Villafranca and his men, on a trial that would take place two weeks after without his presence: the death threats to the pastor. Ari Magnússon, West Fjord district sheriff, wielded the letter by the Danish King that allowed them to kill Basques before twelve judges. And they gave the order.

They had already killed the first ones by then.

Captain Aguirre and Captain Tellería’s crews, 51 men altogether, rowed along the shore in several longboats till they found a sailboat at a small port. They took it, kept sailing along the Icelandic shore, spent several months fishing, stealing sheep, surviving the best way they could, and it is known they got a bigger ship and sailed back to San Sebastián. There is no record of whether they made it.

None of captain Villafranca’s 32 men made it through, however. They scattered in some longboats and one of the groups, composed of 14 men, was caught spending the night in a cabin on the coast. An army of Icelandic peasants stormed the cabin, killed the Basques and tinkered with their corpses for a while. They were “mutilated, defiled, and sunk in the sea, as if they were the worst kind of pagans”, wrote chronicler Gudmundsson, and one can tell he was repulsed by his fellow countrymen and felt compassion for the Basques, who were chased for several weeks throughout Iceland.

In following chapters, the Icelanders found and killed the scattered Basques. They stabbed their eyes, they cut their ears, noses and genitals, and they cut their throats and then tied up the corpses two by two, back to back, paraded them and threw them in the sea.

The final scene places our two main characters facing each other: Captain Martín de Villafranca and Sheriff Ari Magnússon. Villafranca and his remaining two men were inside a cabin, trying to warm up over a fire, when Magnússon’s troops came shooting. The Basque captain yielded and kneeled down before Magnússon and Pastor Grímsson, who had joined him. The account tells Villafranca addressed the pastor in Latin and asked for forgiveness and mercy, the pastor forgave him, and in that same moment one of the Icelanders pounced on the Basque man and took an axe to his chest. Villafranca then sprang up and ran into the shore, dived into the sea and performed a miracle: he swam.

A miracle: Icelanders couldn’t swim. No one swam in that frozen ocean because no one would survive it anyway. The chronicler tells us, brimming with admiration for the Basque captain that Villafranca swam while singing in a strange language the most moving song the Icelanders had ever heard.

The whale is present in many coats of arms of Basque coastal villages

Magnússon’s men didn’t seem too susceptible to beautiful singing, because they jumped onto a longboard, screaming furiously, and rowed towards Villafranca. “He swam like a seal or a trout”, the chronicle goes. One of the Icelanders hit him with a stone to his head, and they picked him up, half dead, from the water. They finished their job thoroughly: they took him to the shore, undressed him, and cut him with a knife from the chest to his navel. Villafranca tried to stand up, Gudmundsson writes, his guts spilling all over. The Basque captain, who was 27 years old, collapsed and died.

The Icelanders laughed at the gutted corpse, “some of them showed curiosity at seeing what’s inside a man”, and then went and killed the two Basques that remained alive. And so they finished the 32 Basque whalers, in the bloodiest massacre in the history of Iceland. They cleaned their knives, Ari Magnússon kept the law that allowed killing Basques in his west fjords domain effective and last week, on April 22, 2015, his successor revoked it.